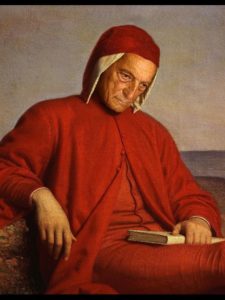

There are moments when I forget what possessed me to read Dante’s Inferno while rehabbing after an injury. It was probably not the best choice to read about navigating the circles of hell while living the ups and downs of rebuilding, trying to decipher mysterious sensations, working through the frustration of feeling very much not like myself, and not always being sure how I will get to where I am going. Then I remember what possessed me to read it: the Irish poet Seamus Heaney. I had just listened to him read his translation of Beowulf and wanted to hear him read something else, anything else, preferably another old story, something far removed from this moment in time. Hearing him read makes the ancient words become relevant and vibrant, and makes me feel more alive in my own skin.

There are moments when I forget what possessed me to read Dante’s Inferno while rehabbing after an injury. It was probably not the best choice to read about navigating the circles of hell while living the ups and downs of rebuilding, trying to decipher mysterious sensations, working through the frustration of feeling very much not like myself, and not always being sure how I will get to where I am going. Then I remember what possessed me to read it: the Irish poet Seamus Heaney. I had just listened to him read his translation of Beowulf and wanted to hear him read something else, anything else, preferably another old story, something far removed from this moment in time. Hearing him read makes the ancient words become relevant and vibrant, and makes me feel more alive in my own skin.

I’d often listen to Heaney read (along with his fellow poets Louise Glück and Robert Pinsky, whose translation it is, and who incidentally wrote one of my favorite poems “Shirt”) on my way home from dropping off my son at school. I could hardly listen to parts of it, so tortured are some of the scenes. Then I’d go inside and sit down to practice, talking myself into blowing freely into the horn without fear of pain or discomfort, deciding which sensations warranted attention and which did not, checking myself in the mirror to make sure things looked normal and easy and ergonomic, recalibrating myself again and again, then I’d lean back in my chair, glance over, and see the cover of Inferno, a shadow figure on the cover bent double in front of a red-orange background, an abstract-ish pitchfork in his back.

I’d ask myself several questions. Couldn’t Pinsky have translated Paradiso first? Why is it that I’m drawn to stories centuries old at this moment? And why am I sitting in this chair again, doing whatever I can to play music again – and not just any music, but, let’s face it, largely old music that fewer and fewer people see the value in?

To attempt to answer the last question – honestly, playing the horn is the only thing I’m formally trained to do, so there’s that. But, of course, it’s more than that. Most of the repertoire is masterful and beautiful, yes. It is worthy of not being forgotten, yes. But the thing is this: music changed me. It made me, over years of steeping myself in it and pursuing it, who I am. It cracked me open and showed me a much wider, more varied and nuanced world than I ever thought possible. In this moment, the old music, the old stories, they show me something larger than this point in time. I can experience humanity, that of others and of myself, in a greater context. (This, by the way, highlights the importance and value of the artistic and musical contributions of our own time – the continuation of the art form.)

Linda Grace, a wonderful Rolfer here in Philadelphia I often go to see, recently suggested I check out the work of Joaquin Farias, a neuroplastician who works with those suffering from dystonia (which is not what I’m dealing with, but I’m finding some of the thoughts in his books to be interesting and potentially helpful). There are some videos on his site that are stunning and inspirational to watch. In one of these videos, a patient giving a TED talk quotes the Italian writer Italo Calvino:

“The hell of the living is not something that will be [italics mine], if there is one; it is what is already here, the hell where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the hell and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and learning: seek to be able to recognize who and what, in the midst of the hell, are not hell, then make them endure, give them space.”

I won’t be overly dramatic by equating my process of rehabbing/rebuilding with hell. It is not that. But it’s not a walk in the park, and it certainly doesn’t feel like time off. It is a multiple-times-daily battle, the effects of which linger and threaten to permeate every moment of my existence if I let it. I’m working on it. I’m also working on toning down the battle imagery. But some days, hell doesn’t feel like a too-distant metaphor. So, if you’ll allow me the first-world exaggeration, supposing this time of recovery/rehab could be equated to some sort of very-mini-hell, what is not hell?

What is most definitely not hell, apart from my loving and supportive family and friends and mentors, are the people who have experienced injuries themselves who, each in their own way, shed light, hope, and possibility. Their stories of finding a way through, and their generosity in sharing them with me, are what I hold onto. They are my lifeline.

So, I am creating a space for them. A website to be exact. I’m collecting stories of those willing to share (anonymously or not) and making a place for this well of knowledge and experience to thrive, providing valuable information, guidance, and hope to those who might find themselves faced with an injury, rehab, or debilitating condition.

So, stay tuned! I hope to write about the website launch in the next month or so. Also, if you are a professional musician interested in contributing your experiences to this project, please contact me.

In the meantime, we’ve begun our yearly trip to Colorado where I’m practicing many times daily and (although Seamus Heaney is, sadly, no longer around to participate in a reading of it) hoping for Robert Pinsky to translate Paradiso very soon.