While flipping through my most recent issue of Ploughshares (a journal I subscribe to), I saw the word “Breath” flash past. As someone who uses her breath for a living, I had to see what this was all about. In scanning the first page, I soon found the words “oboe,” “Mozart,” and “Vermont,” which sealed the deal for me, and I couldn’t help but dive in right away.

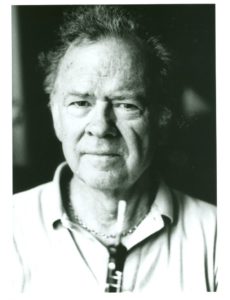

As it turns out, it was written by Mimi Dixon, maiden name Still, daughter of the late Ray Still, principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty years (1953-1993). In this moving essay, she writes about her father, his last days (he died in 2014), the book they were writing together, and her own battle with leukemia. The breath itself is a point of meditation, as well as a device for exploring the powerful presence of her father. Wind and breath weave in and out of stories about her father’s approach to playing the oboe, her own struggles to breathe and stay calm during her illness, and her father’s dying breath.

As it turns out, it was written by Mimi Dixon, maiden name Still, daughter of the late Ray Still, principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty years (1953-1993). In this moving essay, she writes about her father, his last days (he died in 2014), the book they were writing together, and her own battle with leukemia. The breath itself is a point of meditation, as well as a device for exploring the powerful presence of her father. Wind and breath weave in and out of stories about her father’s approach to playing the oboe, her own struggles to breathe and stay calm during her illness, and her father’s dying breath.

She writes, “My father loves singers, absorbs their wisdom about the secrets of the breath, ways to achieve resonance, ease, head tones. The ways they’ve outwitted the body and its limits, so that technique becomes pure music.” She goes on to share how her father thought about oboe technique, and how he taught his oboe students to tell themselves “oboe lies,” tricking the body into being more comfortable. And she has certainly written the most poetic description of a gouging machine and other reed-making devices that one can ever hope to read! Dixon deftly links the relaying of that more technical information with lyrical passages, like one that describes the insects that arrive in her garden on the wind, and another that rubs up against John Donne’s Holy Sonnet. “At the end of this world, will we rise up, inspired and inspirited? But art is the the only true resurrection I know,” she says.

She writes, “My father loves singers, absorbs their wisdom about the secrets of the breath, ways to achieve resonance, ease, head tones. The ways they’ve outwitted the body and its limits, so that technique becomes pure music.” She goes on to share how her father thought about oboe technique, and how he taught his oboe students to tell themselves “oboe lies,” tricking the body into being more comfortable. And she has certainly written the most poetic description of a gouging machine and other reed-making devices that one can ever hope to read! Dixon deftly links the relaying of that more technical information with lyrical passages, like one that describes the insects that arrive in her garden on the wind, and another that rubs up against John Donne’s Holy Sonnet. “At the end of this world, will we rise up, inspired and inspirited? But art is the the only true resurrection I know,” she says.

It’s a beautiful read for musicians and non-musician alike, and, fortunately, the entire essay is available on the Ploughshares website. Enjoy!