Some striking coincidences have occurred in my reading recently. First, back when I had just begun subscribing to literary journals, I received my first issue of the Alaska Quarterly Review in which I found a piece by Eva Saulitis exploring her Latvian heritage. It is a piece that struggles with itself and is not afraid to fragment. It embodies in words the effort to make sense of a complex and broken history. I was taken by the lyricism and beauty of it, even as it deals with the horrors Latvians experienced before and during WWII. Fast forward to last week when I received my most recent copy of The Sun Magazine, which always has an interview feature. This month’s interview was of Eva Saulitis, published posthumously, as she died this year of breast cancer. I began to read the introductory bio and discovered that she began her adult life thinking she would be a musician (an oboist). She attended Northwestern University on a music scholarship, however, a couple years into her degree, found her true calling and left to study marine biology, later becoming a writer and poet as well. As I read her biography, I couldn’t help but wonder, was there something in her writing that attracted my musical soul to hers through the written word? After her cancer diagnosis she, of course, continued to write, offering up the difficult and irreconcilable bits of her life and family history, turning them into art.

The next big coincidence: when I was in high school I chose Carson McCullers’ book The Heart is a Lonely Hunter as my subject for an English paper. I don’t know how or why I came to choose it, but I did. Again, fast forward. This month, AGNI, another journal I subscribe to, published a piece written by a Swiss writer, Annemarie Schwarzenbach, who wrote in 1940 about Carson McCullers, shortly after The Heart is a Lonely Hunter was published. They had recently met and had started corresponding. In a letter to Schwarzenbach, McCullers describes how she woke up thinking about the Brahms Violin Sonata in D Minor and how happy she had been feeling since then. (Incidentally, or maybe not so incidentally, I discovered while brushing up on Carson McCullers’ bio, that she initially had plans to become a pianist, and perhaps to study at Juilliard, but either illness or her desire to write got in the way – the details are unclear in my sources). She goes on to try to explain to Annemarie what she wants to accomplish in her future writing and then writes, “Maybe a decade from now all the good people will be dead.”

Schwarzenbach is struck by this statement, and how such a sense of despair could come from one living happily in New York after the resounding success of a book. But she understands the despair, this being 1940, with Schwarzenbach’s home continent in tatters. She writes, “a whole future generation of musicians, painters, poets, and inventors, an unknown number of young talents, an army of dead, are laid out on the battlefield.” She goes on to say that, in the time she spent with McCullers, it was clear they were of the same mind about “the endless struggle to express life fully while at the same time living it to the full, however one can.” Schwarzenbach concludes, “I spent five weeks in New York, far from the battlefront, among well-meaning people, with that enormous city of the future and its limitless potential at my feet. So why this paralyzing despair?… On the lush green bank of this great river, under fleeting clouds of June, I no longer know. And wonder if it’s worth taking up my pen, and yet I do.”

The coincidences of these authors’ musical biographies and references are what caught my attention at first, of course, but the real message that the serendipitous convergence of these voices brings to me goes much deeper. What inspires me is that, in the face of all that the world holds (success, illness, music, war, disasters), and in the midst of all our responses to what the world holds (delight, fear, love, despair, grief) these women, Eva Saulitis, Carson McCullers, and Annemarie Schwarzenbach, consciously chose to keep taking up their instrument of choice – the pen in their case – time and time again. Their lives and circumstances were complex, messy, and wildly imperfect, but their art served as a way to keep going forward, to try to express the fullness of existence. As writers, they could document, remember, and communicate in more exact ways than we musicians can, but in a certain way it is the same across all art forms, in that a space is being created where life can be more fully contemplated – and shared – imperfections and all. The simple fact of their words’ arrival into my life, in addition to the life-giving qualities that I see music (and other creative work) bringing to my life and others’ lives every day, confirms to me that continuing to pick up our instruments – whatever musical or non-musical instruments they may be – is what we must do, in whatever way we can.

The last two lines of that first piece I ever read by Eva Saulitis (“Third Person Displaced”) that I loved so much:

You must make something of this, however broken.

And then you must tell them.

May we all follow their lead, making something from the fragments of whatever surrounds us – and share it.

For those of you following the story of Baset, the young Afghan trumpet player that my husband has been mentoring, it has been a whirlwind of activity for him recently. Baset graduated from Interlochen Academy of the Arts in May, an accomplishment that was a mere dream two years ago as a student in Kabul. He received a full scholarship to the University of Kansas, but needed to raise the money for four years’ worth of living expenses and incidentals. Since his new GoFundMe campaign began, over one thousand people have donated. The outpouring of generosity has been overwhelming and heartening, especially during this time when it is very easy (for me, at least) to get caught up in fear and despair, looking at what is wrong with humanity and worrying about the seemingly unsolvable problems of our world. I am so thankful for Baset – thankful that he had the courage to dream and reach for something that many people might have thought impossible. I am so thankful for the thousands of people who have donated amounts, large and small, so that a young musician from a ravaged country can be given a chance to thrive. The efforts of so many people have come together to create a miracle.

For those of you following the story of Baset, the young Afghan trumpet player that my husband has been mentoring, it has been a whirlwind of activity for him recently. Baset graduated from Interlochen Academy of the Arts in May, an accomplishment that was a mere dream two years ago as a student in Kabul. He received a full scholarship to the University of Kansas, but needed to raise the money for four years’ worth of living expenses and incidentals. Since his new GoFundMe campaign began, over one thousand people have donated. The outpouring of generosity has been overwhelming and heartening, especially during this time when it is very easy (for me, at least) to get caught up in fear and despair, looking at what is wrong with humanity and worrying about the seemingly unsolvable problems of our world. I am so thankful for Baset – thankful that he had the courage to dream and reach for something that many people might have thought impossible. I am so thankful for the thousands of people who have donated amounts, large and small, so that a young musician from a ravaged country can be given a chance to thrive. The efforts of so many people have come together to create a miracle.

“It is not a requiem to console the living. Sometimes it does not even help the dead to sleep soundly.” – The Times

“It is not a requiem to console the living. Sometimes it does not even help the dead to sleep soundly.” – The Times As it turns out, it was written by Mimi Dixon, maiden name Still, daughter of the late Ray Still, principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty years (1953-1993). In this moving essay, she writes about her father, his last days (he died in 2014), the book they were writing together, and her own battle with leukemia. The breath itself is a point of meditation, as well as a device for exploring the powerful presence of her father. Wind and breath weave in and out of stories about her father’s approach to playing the oboe, her own struggles to breathe and stay calm during her illness, and her father’s dying breath.

As it turns out, it was written by Mimi Dixon, maiden name Still, daughter of the late Ray Still, principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty years (1953-1993). In this moving essay, she writes about her father, his last days (he died in 2014), the book they were writing together, and her own battle with leukemia. The breath itself is a point of meditation, as well as a device for exploring the powerful presence of her father. Wind and breath weave in and out of stories about her father’s approach to playing the oboe, her own struggles to breathe and stay calm during her illness, and her father’s dying breath. She writes, “My father loves singers, absorbs their wisdom about the secrets of the breath, ways to achieve resonance, ease, head tones. The ways they’ve outwitted the body and its limits, so that technique becomes pure music.” She goes on to share how her father thought about oboe technique, and how he taught his oboe students to tell themselves “oboe lies,” tricking the body into being more comfortable. And she has certainly written the most poetic description of a gouging machine and other reed-making devices that one can ever hope to read! Dixon deftly links the relaying of that more technical information with lyrical passages, like one that describes the insects that arrive in her garden on the wind, and another that rubs up against John Donne’s Holy Sonnet. “At the end of this world, will we rise up, inspired and inspirited? But art is the the only true resurrection I know,” she says.

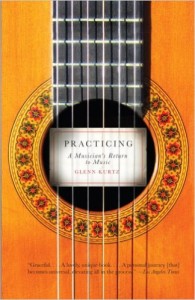

She writes, “My father loves singers, absorbs their wisdom about the secrets of the breath, ways to achieve resonance, ease, head tones. The ways they’ve outwitted the body and its limits, so that technique becomes pure music.” She goes on to share how her father thought about oboe technique, and how he taught his oboe students to tell themselves “oboe lies,” tricking the body into being more comfortable. And she has certainly written the most poetic description of a gouging machine and other reed-making devices that one can ever hope to read! Dixon deftly links the relaying of that more technical information with lyrical passages, like one that describes the insects that arrive in her garden on the wind, and another that rubs up against John Donne’s Holy Sonnet. “At the end of this world, will we rise up, inspired and inspirited? But art is the the only true resurrection I know,” she says. I have read a fair amount of musicians’ biographies and memoirs over the years, though not so many recently, as my curiosities and interests often take me far from music. A couple months ago, however, someone recommended to me a memoir by Glenn Kurtz called

I have read a fair amount of musicians’ biographies and memoirs over the years, though not so many recently, as my curiosities and interests often take me far from music. A couple months ago, however, someone recommended to me a memoir by Glenn Kurtz called